Gold reserves come back #2

Written by Marwane Khalloufi, Financial Analyst, CFA

Why sovereigns are buying, and a new player in town

For most of the post-Bretton Woods era, gold sat in central-bank vaults as a legacy asset: politically symbolic, occasionally useful for confidence, but rarely “active.” That changed sharply after the Global Financial Crisis, and then again after the 2022 Russia’s sanctions shock. Today, gold has re-emerged as a strategic reserve asset for sovereigns, and increasingly for large private balance sheets that function like quasi-financial infrastructure.

One of the most interesting example is Tether, issuer of USDT (a stablecoin), whose reserve disclosures now explicitly include LBMA standard physical gold bars as part of the reserves backing its fiat-denominated tokens.

1) The sovereign gold bid: from “barbarous relic” to strategic asset

A structural shift, not a “trade” that translates into “High, sustained” central-bank buying is now normal

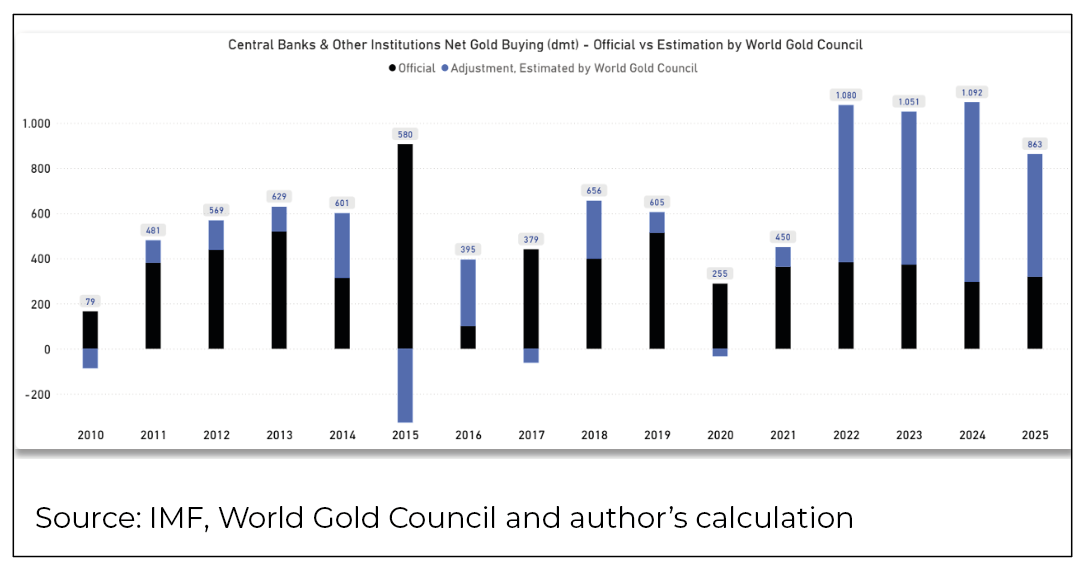

World Gold Council (WGC) data shows that official-sector demand remains structurally elevated. In the year 2025, buying stood at 863 tonnes, roughly 30% of the annual gold production worldwide!

WGC’s Central Bank Gold Reserves Survey 2025 also points to more active gold management, with risk management rising in prominence among reasons for holding gold.

One notable nuance: reported reserve data can lag, differ by accounting conventions, or understate activity if purchases are routed through intermediaries. That’s one reason WGC and ECB analyses often discuss both “reported” flows and broader demand indicators. Based on the world gold council data, the real gold buying by central banks around the world would be as below :

The negative adjustment are usually coming from reporting lags from certain countries with Chine for example in 2015 where they reported purchases for the first time in 6 years. Looking at the chart, 2022 strikes as being a deciding year.

The World Gold Council estimates central banks bought around 1,080 tonnes in 2022 and 1,051 tonnes in 2023, followed by another year above 1,000 tonnes in 2024. 2025 is below 1000 tonnes with 863 tonnes of purchases but still substantially above pre-2022 levels.

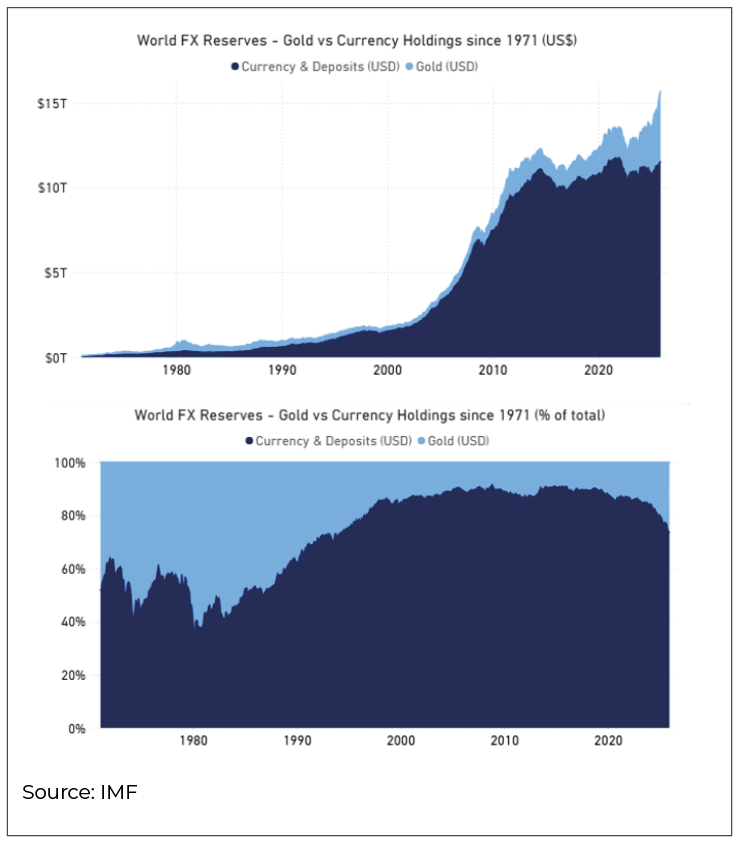

The European Central Bank (ECB) frames this as part of a broader reconfiguration of reserve portfolios: at market value, gold’s share of global official reserve holdings reached ~20% and surpassed the euro (~16%). More on the share of gold inside FX Reserves later.

The “why” in three powerful incentives

- 1) Sanctions risk and “asset seizure awareness”

Gold is a reserve asset that is no one else’s liability. It can’t be frozen through a correspondent banking chain in the same way that deposits, securities held at custodians, or reserve accounts can. The ECB explicitly links the post-2022 environment to historically large official gold purchases, especially among countries that are more geopolitically distant from the West.

- 2) Diversification away from concentrated FX exposure

Many central banks still hold large allocations to USD assets, gold offers a way to reduce reliance on any single issuer, legal jurisdiction, or settlement network, without needing to “pick” another currency bloc.

- 3) Crisis insurance and credibility

Gold functions as a confidence asset in periods of high inflation uncertainty, war risk, or domestic currency stress. It can support external credibility (and sometimes domestic legitimacy) because it is universally recognized collateral.

Gold accumulation is often not explained by “returns,” but by a state’s preferred monetary posture:

- Insurance against external pressure (sanctions/asset freezes).

- Confidence signaling (domestic and international).

- Collateral logic (gold’s usability in stress conditions).

- Long-run monetary optionality (in a world of high public debt and politicized finance).

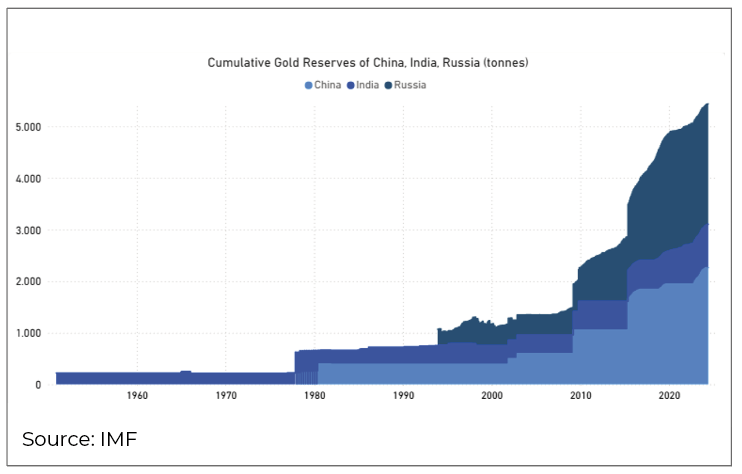

The result: gold is increasingly treated as strategic balance-sheet sovereignty rather than a commodity bet. To put it bluntly: Gold is money. To illustrate this, we can look at the below chart which displays three major powers that need this neutral asset to be shielded from sanctions on paper assets detained in unfriendly places: the gold reserves of China, India & Russia.

The storage location is crucial. As the saying goes, “if you don’t hold it, you don’t own it”. You are not free from sanctions if the gold is stored outside of your country but rather at the mercy of the storing country. A few episodes of gold repatriation can showcase this idea. It is rarely a simple logistics exercise, it is a stress test of custody, politics, and legal recognition. Germany’s Bundesbank faced years of domestic scrutiny over auditability and access before ultimately completing the relocation of gold from New York and Paris to Frankfurt ahead of schedule, a program explicitly designed to strengthen operational control in a crisis.

In more contentious cases, repatriation can turn into outright litigation: Venezuela’s attempt to regain access to roughly $1bn of gold held at the Bank of England has been tied up in UK courts for years, hinging on which authorities the UK recognizes as entitled to give instructions over the reserves. Even where relations are cooperative, official reviews can still trigger politically sensitive moves, Austria, after audit and risk-concentration concerns, formally shifted its storage strategy to bring a larger share of its gold closer to home rather than relying predominantly on foreign vaults.

This subject of gold stored in New York and London also leads to another subject; that of gold leases and swaps (in a way, fractional gold banking). But that is a topic for another time.

The most common storage locations for private individuals illustrate this need for security and respect of private property. As an example, Switzerland is often the chosen location due to its role in wealth management thanks to its tradition of private banking, its stable political landscape helping to foster trust in the legal system and finally its famous neutrality. Additionally, it has the particularity of being a dominant player in the gold refining sector. Or that can be seen as a consequence of the enumerated points above.

2) Tether’s USDT reserve stack now includes substantial physical gold

To describe what Tether is, let’s quote their presentation on their website :

“Tether tokens offer the stability and simplicity of fiat currencies coupled with the innovative nature of blockchain technology, representing a perfect combination of both worlds.

So just like a bank, Tether issues fiat money represented in digital tokens called USDTs.

Lately, Tether made noise in the precious metals sector as its own reserve reporting for the entity issuing its fiat-denominated tokens explicitly lists “Precious Metals” as part of the reserves backing those tokens, and defines that category as LBMA standard physical gold bars.

This is a significant story due to the size of Tether’s assets. It is now basically a bank which issues its own bank notes backed mainly by US treasuries and the rest being gold, bitcoin and gold equities.

To give a sense of scale: press reports in late January 2026 described Tether as holding gold on the order of ~100–130 tonnes (depending on the reporting cut-off and valuation), putting it in the same league as the official reserves of some mid-sized countries.

What the reserve reports say :

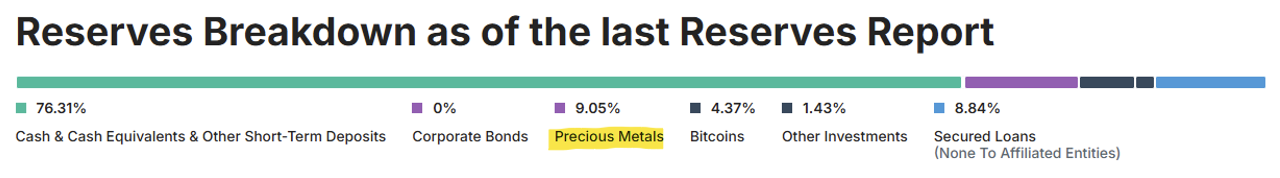

In Tether’s “Financial Figures and Reserves Report”:

- As of 30 June 2025, “Precious Metals” were US$ 8.725 billion within total reserves of US$ 162.575 billion.

- As of 30 September 2025, “Precious Metals” were US$ 12.921 billion within total reserves of US$ 181.223 billion.

- As of 31 December 2025 (the latest report available at the time of writing), “Precious Metals” were US$ 17.450 billion within total reserves of US$ 192.878 billion (about 9.0% of reserves).

And the report is unusually explicit on what that gold is:

“Precious Metals” comprises LBMA standard physical gold bars owned by Tether International.

Custody and location matter: in interviews reported in late January 2026, Tether’s CEO said some of the company’s gold is stored in Switzerland in a heavily secured, former Cold War / nuclear bunker-style facility—chosen for physical security, legal certainty, and operational control.

Two important takeaways from their report :

- USDT is still predominantly backed by very short-duration USD liquidity

The same disclosures show the biggest reserve component is U.S. Treasury bills and cash-equivalent structures (including repos and money-market funds).

So: yes, USDT reserves include a lot of gold in absolute dollars (~$17B), but it is not the majority of the backing.

- Tether is behaving like an “official sector” allocator

The scale and framing make Tether look less like a fintech and more like a balance-sheet institution that is building a hard-asset sleeve alongside a large U.S. Treasury portfolio.

3) Tether also enters the royalty & streaming sector

Tether’s appetite is getting bigger as it (through affiliated entities) has made multiple disclosed investments in listed royalty/streaming companies. A quick summary below:

Elemental Altus Royalties

Tether announced it acquired a substantial stake to deepen its push into gold and “hard-asset backed financial infrastructure.”

In 2025, Elemental Altus and EMX Royalty announced a merger to form a mid-tier gold-focused royalty company, with a $100 million cornerstone investment from Tether cited in deal reporting and legal/deal summaries.

Versamet Royalties

Versamet’s own release states Tether acquired 11,827,273 shares (~12.7%) as a cornerstone shareholder.

A Canadian transaction notice gives the purchase price detail: CAD$103,488,638.75 at CAD$8.75/share, again referencing ~12.7%.

Gold Royalty Corp

Tether-related entities filed a Schedule 13D showing ownership of 13.1% based on shares outstanding referenced in the filing.

Metalla Royalty & Streaming (MTA)

A Schedule 13D filing relates to holdings in Metalla for around ~8.9% of the company’s shares.

4) Why royalty & streaming is the “bridge” between reserves and real-world gold supply

If you want gold exposure without running a mine, you have four broad routes:

- Physical bullion (simple, liquid, but no yield).

- Mining equities (high beta, operational and political risk).

- Gold loans/structured credit (counterparty risk).

- Royalties & streams (long-duration exposure to production with limited operating risk).

Royalty & streaming is the closest thing the gold world has to an “infrastructure asset”: you finance projects and receive a contractual claim on future production or revenue.

That is why this sector is a natural destination for a large balance sheet trying to “own gold in a productive way” without becoming a miner. It also helps avoid storage costs on bullion.

Why this strategy “rhymes” with sovereign gold accumulation

Sovereigns buy gold to reduce dependence on foreign liabilities.

Royalties/streams extend that logic:

- Bullion is a stock of wealth.

- Royalties/streams are a claim on future metal flows, a way to “own” production upside without operating the asset.

For a balance sheet like Tether’s, large, liquid, and exposed to regulatory shifts, royalties can look like a productive hard-asset reserve: potentially durable, globally diversified, and less correlated to the same levers that govern fiat liquidity markets.

5) What changes if a stablecoin issuer becomes a major gold allocator?

A new kind of “official sector” participant

Traditionally, the big marginal buyers of physical gold were:

- central banks,

- jewelry demand (price sensitive),

- ETFs and institutional investment demand (risk-on/risk-off),

- OTC flows.

If a stablecoin issuer with very large reserves decides to carry single-digit percent (and skewing towards double digits) of backing in gold, that creates a new channel:

digital-dollar adoption → reserve growth → incremental gold demand.

That is not inherently good or bad but it is structurally different, because it links gold demand to the dynamics of stablecoin issuance and redemption. This is also true for bonds, as the interest shown by the US government proves. Stablecoins could be a massive tool used to finance the huge debt load of the bleeding public finances. This evolving situation must be followed with great attention as the biggest bond market in the world looks for financing.

6) The Big Picture

In the end, the come back of both nations and major financial entities to the gold market by accumulation is linked to their need to construct sound and credible reserves for their country or corporate entity.

One of the best ways to observe this is to take the global foreign exchange reserves composition globally. We can see the clear diminution of gold inside the world reserves after 1980 and we can now smell the beginning of a major shift. According to modern financial thinking, gold went from being central prior to 1971 to only a simple and useless “pet rock”. We can only assert that its recent price behaviour is a loud statement for who cares to listen and that this modern thinking is perhaps very wrong. A question to answer: what options do wealth and reserves managers have in a polarized world where financial repression is looming if not already in place in many countries?

Bonds are not likely to be the answer as high debt burdens forces the hand of central banks and governments to suppress interest rates. And if they do not act that way, the consequences of a free bond market could induce severe losses (due to rising rates) and naturally make the weight of gold go up in the reserves as bonds prices go down. Either way, gold seems to be a great asset for such times.

To conclude and display this shift, let’s visualize the world foreign exchange reserves split between gold and currency holdings (mainly bonds) between 1971 and the latest data available (January 2026).