Gold Reserves Mismanagement #1

Written by Marwane Khalloufi, Financial Analyst, CFA

Gold is sometimes referred to as a “pet rock”, a useless metal. Monetary History and central banks tell a different story. The last century shows that official gold holdings are shaped as much by monetary regimes and institutional mechanics as by actual buying and selling. Some of the biggest “moves” in reserve were triggered not only by trucks and planes moving bullion, but by policy resets, coordinated official programs, and at times accounting structures that temporarily reshuffled how gold was reported.

1) From gold anchor to fiat reality: Roosevelt, Bretton Woods, and the “Nixon Shock”

The modern story begins with a decisive US reset. The Gold Reserve Act of 1934 centralized monetary gold at the US Treasury and formalized the revaluation framework that helped reshape the monetary system in the 1930s.

After WWII, Bretton Woods made the dollar the fulcrum: currencies were pegged to the dollar, and foreign monetary authorities could convert dollars into US gold at the official price. That structure carried a built-in contradiction: as global trade grew, the world needed more dollars, but more dollars held abroad increased claims on a finite US gold stock. The strain surfaced dramatically in the 1960s.

To defend the official price, central banks formed the London Gold Pool (1961–1968), a coordinated intervention effort to keep gold at $35/oz through sales and purchases in London. It worked for several years, then collapsed in March 1968 under pressure and disagreement among participants. France was a notable dissenter in the Gold Pool and was one of the first countries to ask for conversion of their dollar reserves into gold and repatriation.

The endgame arrived on 15 August 1971, when President Nixon suspended official convertibility, widely known as the “Nixon Shock” or “closing the gold window.” The Federal Reserve’s historical account frames this as a response to a looming gold run and domestic inflation pressures; Nixon’s own address announced the suspension directly.

2) The 1970s weren’t “free market only”: volatility and coordinated official actions

A common misconception is that once Bretton Woods broke, gold immediately became purely a private-market story. In reality, the 1970s were full of official-sector actions, often structured, multi-year, and explicitly coordinated.

A central example: the IMF’s 1976-1980 gold auctions, designed to sell part of IMF holdings via a planned program. Contemporary IMF reporting describes a four-year auction plan totaling 25 million ounces.

In volatile regimes, reserve series can show clusters of moves that reflect policy-era programs rather than organic buying/selling decisions made in isolation.

Not every increase in reported gold reserves reflects physical accumulation.

During the European Monetary System era, some reserve movements were tied to official ECU swap mechanics. A clean, primary-source statement comes from the Central Bank of Ireland’s 1998 Annual Report, which explains that the Bank participated in quarterly swaps exchanging 20% of its gold and US dollar holdings for official ECU, and that these swaps were unwound on 31/12/1998.

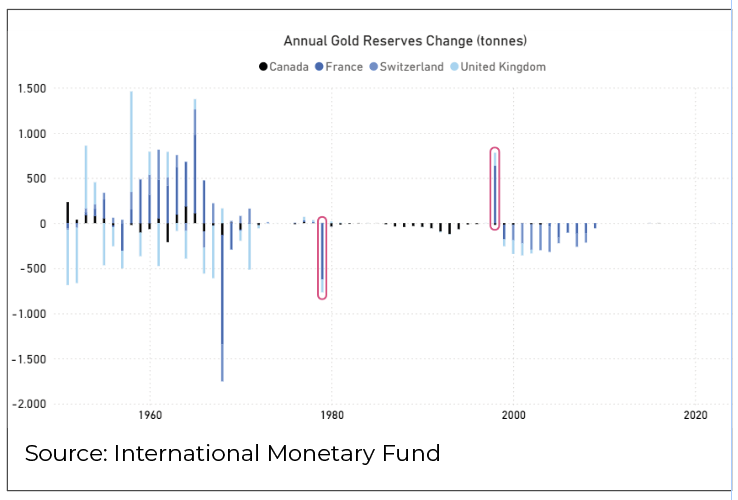

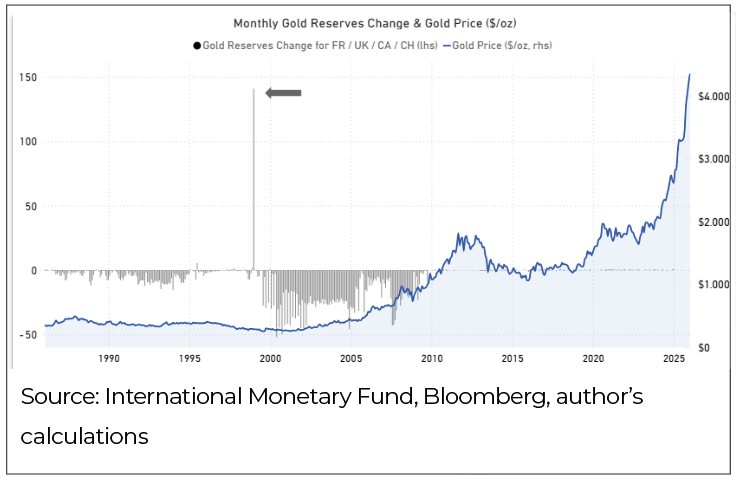

Part of the apparent late-1990s shift in some European gold reserve series reflects the unwinding of ECU-era swaps, not a sudden wave of physical purchases. This is highlighted below with the start and end of ECU system (bar circled in red).

3) The 1990s–2000s sell-down: “Brown’s Bottom,” Swiss sales, and Canada’s near-zero endpoint

The UK: “Brown’s Bottom”

The UK’s 1999–2002 gold auctions are among the most famous reserve management episodes precisely because they became a nickname: “Brown’s Bottom” (a shorthand used by market participants to describe selling near a cyclical low). Gordon Brown was Chancellor of the Exchequer at the time (equivalent to the Treasury Secretary in the US).

The hard facts are unusually well documented. The UK government confirms that ~395 tonnes were sold across 17 auctions run by the Bank of England on the Treasury’s behalf. The Bank of England also published a detailed analysis of those auctions.

Switzerland: sales only after the “gold-standard relics” were removed

Switzerland’s case is structurally different and more institutional. The Swiss National Bank notes it was only in May 2000 that the last remnants of gold-standard constraints were removed from the legal framework, enabling sales and then completing a 1,300-tonne program by March 30, 2005. As a matter of fact, the Swiss Franc is a unique currency due its history and financial performance. Other from being one of the strongest and reliable currency in the world, it was then only currency in the western world to be on the gold standard until 1999 when Switzerland joined the IMF. The latter forbids the backing of currencies by gold for its members.

Canada: “and then there was none”

Canada illustrates the extreme endpoint of the “gold is unnecessary” philosophy. Today, Canada’s gold holdings stood at 0 tonnes of gold; The selling started in the end of 1980s bringing the reserves to insignificant levels by early 2000s.

The coordinating framework: the Washington Agreement / CBGA

A key reason the late-1990s official sales didn’t become disorderly is that they were explicitly structured. The ECB’s 26 September 1999 joint statement (the Washington Agreement / Central Bank Gold Agreement) stated that annual sales would not exceed ~400 tonnes, and total sales over five years would not exceed 2,000 tonnes.

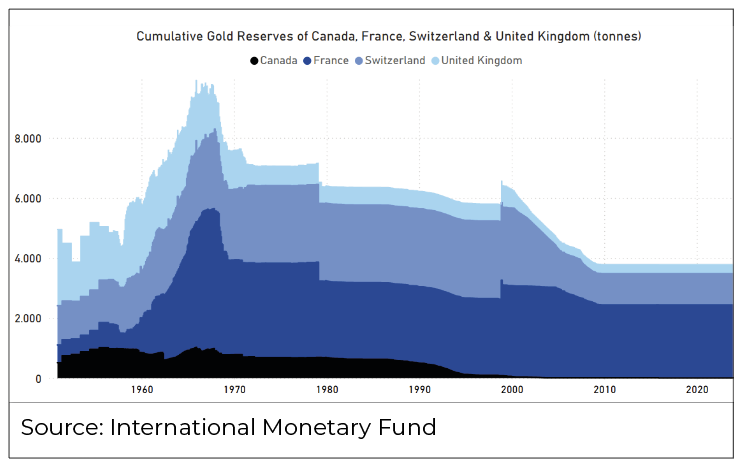

Below is the illustration of the reserves’ evolution of these four countries:

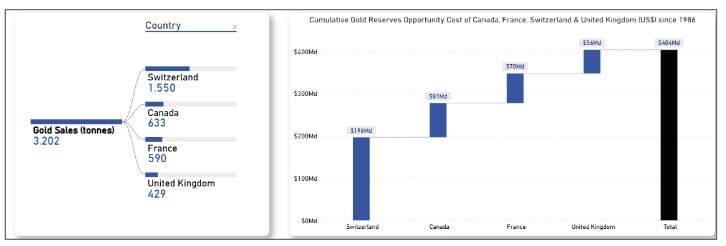

4) “Missing tonnes” is not a metaphor: it becomes a measurable opportunity cost

Reserve management is a long-duration decision. When a country sells a strategic reserve asset in size, it is not simply reducing volatility in a quarterly portfolio report; it is choosing a path through future regime uncertainty. And when the regime changes, as it did after the late 1990s, the difference between holding and selling can become visible on the scale of hundreds of billions. Thanks to publicly available gold reserves numbers, we calculated the opportunity cost coming from the untimely sales of gold reserves by France, Canada, Switzerland and the UK. (From 1986 to October 2025):

To illustrate better the bad decision making, the below chart plots both sales and gold price since 1986 (reminder: the big spike in gold reserves being the accounting adjustment of the European Monetary System):

The amounts are all but insignificant, these four countries cumulate more than $460 Billions of lost gains from their sales of gold reserves! Switzerland case is quite impressive, especially knowing the tradition of prudence and independence of the Helvetians. Their gold opportunity cost is almost equal to their federal debt.

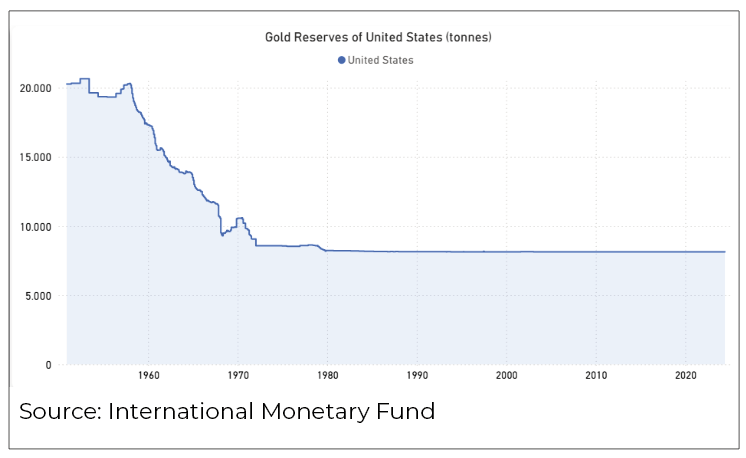

It is also ironic to observe that meanwhile these major US allies sold all or parts of their gold reserves, the United States did not participate in the sales after 1980. The superpower has been acting to support the strength of its currency through diverse forms over the last decades (petrodollar, Extraterritoriality of the US$…) and insisting on gold being a barbaric relic was part of it. But in the end, only the naive allies sold and Washington remains with its reserves untouched (as per the public records, some suggest actual numbers at Fort Knox might differ from the disclosed amounts).

Finally, one can imagine the pain coming from the opportunity cost for these countries and sadly for them it will likely increase thanks to the usual mismanagement of not only gold reserves but currencies, public debts and budgets.

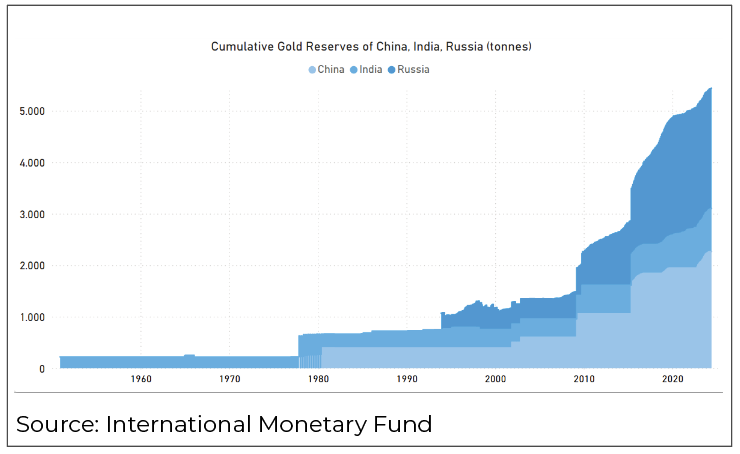

Meanwhile, lots of gold has been flowing east lately…

To follow: #2 Gold Reserves are Back